Performance Measures For Business Developers

The lack of well-defined performance criteria causes many business development practitioners to operate blindfolded, never really knowing whether they are successful at what they do or not. Tracking the performance of business development units and setting up performance measures for them is necessary to mature business development as a discipline rather than operating it as a magic cure-all bullet."Tracking the performance of business development units and setting up performance measures for them is necessary to mature business development as a discipline rather than operating it as a magic cure-all bullet"

The tasks at hand are often diffuse and ad hoc, and they are rarely planned in advance. Therefore, setting up performance measures is a way of clarifying goals, documenting effect and aligning expectations – in particular important to enable long-term planning in the unpredictable and changeable operating environment of today's business development units.

The tasks at hand are often diffuse and ad hoc, and they are rarely planned in advance. Therefore, setting up performance measures is a way of clarifying goals, documenting effect and aligning expectations – in particular important to enable long-term planning in the unpredictable and changeable operating environment of today's business development units.However, defining universal performance measures and report metrics that are viable for all business development units is an impossible mission due to the diversity of business development practices. Again, the analogy from the discipline of HR and HRM may serve as a point of departure. As HR has matured and become an integrated organisational discipline, a framework for measuring the value and performance of a successful HR function has been derived. This framework measures the management's and the organisation's overall satisfaction level with the work performed by the HR function as well as a range of specific and directly measurable metrics.

To work effectively, performance measures for business development must allow for

o Clear accountability for the team and their individual contributions.

o Measurable business impact through consistent project evaluations.

o Consistent and demanding standards for each job role fulfilled.

o Procedures for communicating and rewarding the right results.

Performance measures in a BDM context

With the roles as strategists, executors and facilitators come different kinds of requirements, and these requirements may be translated into different kinds of performance measures.

In the figure below, you will find an inspirational list of key success factors and examples of KPIs for each of the three roles played by business developers (strategist, executor and facilitator).

A systematic approach to measuring the effort of business development units is something that is rarely seen in practice. Some units may have some metrics that they use for their work, but these are often randomly defined from project to project and not formally integrated in the processes within the unit.

"To ensure performance over time, that the unit remains proactive and that the learnings are picked up and reacted upon, performance measures must be an integral part of the work of the unit"

Whereas this may work for a limited period of time and when projects are somewhat similar, it is not sustainable. To ensure performance over time, that the unit remains proactive and that the learnings are picked up and reacted upon, performance measures must be an integral part of the work of the unit.

• Facilitate and challenge the long-term planning efforts to turn these investments into profitable new business

Following these simple guidelines, the company was able to define a set of very precise performance metrics against which the success or failure of the business development investment could be measured, including

• Number of identified candidates within the three areas of focus

• Number of right companies at the negotiation table

• Number of new licensing activities completed

• Number of new patent rights acquired

• ROI of commercialised in-licensed activities

• Management assessment of quality and speed of execution

Describe Your Business

This is a good time to explain your company and some of its underlying strategy, such as competitive edge and value proposition, as well as establishing base-line numbers for your plan.I find switching modes like this, from numbers to text and back, helps keep the process fresh as you develop your plan. This chapter will cover a table or two, either past performance or start-up costs, depending on your specific plan.

You’re probably noticing by now that developing a business plan doesn’t really happen in a straight logical order of steps. It isn’t really a sequential process. For example, you looked at your market numbers first while doing the Initial Assessment, The MiniPlan, and will again as you focus on more detail for the Market Analysis topic. You’ll probably visit those numbers again as you do the Industry Analysis. In coming chapters you’ll project your sales, personnel, and profits, but you’ll probably have to revise those numbers when you look at your balance sheet and cash flow.

If you are starting a business, please go now to Starting a Business dedicated to issues in starting a business. I don’t want to interrupt the flow of the plan with that discussion at this point, particularly for those who are working on an ongoing business. However, if you are starting a business, and haven’t read please read that chapter now and then return here.

Company Information

As discussed earlier Pick Your Plan, my recommended business plan outline includes a chapter topic on your company, right after the Executive Summary. I pointed out then that you may not need to include this chapter if you are writing an internal plan. However, any outsiders reading your plan will want to know about your company before they read about products, markets, the rest of the story.

Summary Paragraph

Summary Paragraph Summary Paragraph Summary Paragraph Summary Paragraph Start the chapter with a good summary paragraph that you can use as part of a summary memo or a loan application support document. Include the essential details, such as the name of the company, its legal establishment, how long it’s been in existence, and what it sells to what markets.

Legal Entity / Ownership

In this paragraph, describe the ownership and legal establishment of the company. This is mainly specifying whether your company is a corporation, partnership, sole proprietorship, or some other kind of legal entity, such as a limited liability partnership. You should also explain who owns the company, and, if there is more than one owner, in what proportion.

If your business is a corporation, specify whether it is a C (the more standard type) or an S (more suitable for small businesses without many different owners) corporation. Also, of course, specify whether it is privately owned or publicly traded.

Many smaller businesses, especially service businesses, are sole proprietor businesses. Some are legal partnerships. The protection of incorporating is important, but sometimes the extra legal costs and hassles of turning in corporate tax forms with double-entry bookkeeping are not worth it. Professional service businesses, such as accounting or legal or consulting firms, may be partnerships, although that mode of establishment is less common these days. If you’re in doubt about how to establish a start-up company, consult a business attorney.

Locations and Facilities

Locations and Facilities Briefly describe offices and locations of your company, the nature and function of each, square footage, lease arrangements, etc.

If you are a service business, you probably don’t have manufacturing plants anywhere, but you might have Internet services, office facilities, and telephone systems that are relevant to providing service. It is conceivable that your Internet connection, as one hypothetical case, might be critical to your business.

If you’re a retail store, then your location is probably a critical factor, so explain the location, traffic patterns, parking facilities, and possibly customer demographics as they relate to the specific location (your Market Analysis goes elsewhere, but if your shopping center location draws a particular kind of customer, note that here).

If you are manufacturing, then you may have different facilities for production, assembly, and various offices. You may have manufacturing and assembly equipment, packing equipment, docks, and other facilities.

Depending on the nature of your plan, its function and purpose, you may want to include more detail about facilities as appendices attached to your plan.

For example, if your business plan is intended to help sell your company to new owners, and you feel that part of the value is the facilities and locations, then you should include all the detail you can. If you are describing a manufacturing business to bankers or investors, or anybody else trying to value your business, make sure you provide a complete list and all necessary detail about capital equipment, land, and building facilities. This kind of information can make a major difference to the value of your business. On the other hand, if your business plan is for internal use in a small company with a single office, then this topic might be irrelevant.

Think Strategically

One of the most valuable benefits of developing a business plan is thinking in depth about your company. You started that as part of The MiniPlan, as you entered drafts of your objectives, mission statement, and keys to success. A standard plan also includes sections in the strategy chapter that provide deep background for strategy. This is a good point for developing those texts.

Value Proposition

Value Proposition Value Proposition Value Proposition Value Proposition Value-based marketing is a useful conceptual framework. The value proposition is benefit offered less price charged, in relative terms. For example, the auto manufacturer, Volvo, has for years offered a value proposition based on the value of safety, at a price premium. A more detailed discussion of this framework can be found in Strategy Is Focus.

Competitive Edge

Competitive Edge Competitive Edge Competitive Edge Competitive Edge So what is your competitive edge? How is your company different from all others? In what way does it stand out? Is there a sustainable value there, something that you can maintain and develop over time? The classic competitive edges are based on proprietary technology protected by patents. Sometimes market share and brand acceptance are just as important, and know-how doesn’t have to be protected by patent to be a competitive edge.

For example, Apple Computer for years used its proprietary operating system as a competitive edge, while Microsoft used its market share and market dominance to overcome Apple’s earlier advantage. Several manufacturers used proprietary compression to enhance video and photographic software, looking for a competitive edge.

The competitive edge might be different for any given company, even between one company and another in the same industry. You don’t have to have a competitive edge to run a successful business—hard work, integrity, and customer satisfaction can substitute for it, to name just a few examples—but an edge will certainly give you a head start if you need to bring in new investment. Maybe it’s just your customer base, as in the case with Hewlett-Packard’s relationship with engineers and technicians, or it’s image and awareness, such as with Compaq. Maybe it is the quality control and consistency of IBM.

The most understandable of the competitive edges are those based on proprietary technology. A patent, an algorithm, even deeply entrenched know-how, can be solid competitive edges. In services, however, the edge can be as simple as having the phone number 1 (800) SOFTWARE, which is an actual case. A successful company was built around that phone number.

Baseline Numbers

While we’re focusing on the company description, let’s establish the starting numbers that form the basis of your cash flow and balance sheet in ongoing companies, your starting balance for the future is the last balance from the past.

Past Performance for Past Performance for Ongoing Companies

Past performance explained here is for ongoing companies. If you are a start-up business, skip to the section called Start-up Costs for Start-up Companies.

Important past performance items can be typed into the past performance worksheet. They are used for comparing past performance to projected future, and to establish your starting balances.

Ongoing companies need to include a summary of company history, as a topic in your text. If you are an ongoing company, then you’ll need to present financial results of the recent past, and this text section is where you explain them.

Explain why your sales and profits have changed. If you’ve had important events like particularly bad years or good years, or new services, new locations, new partners, etc., then include that background here. Cover the founding of the company, important events, and important changes.

Your first consideration is the needs of your reader. This isn’t a history assignment. Give the reader of the business plan the background information he or she needs to understand your business.

For your financial analysis as an ongoing company, you will want to make sure you have some very important highlights of your company’s past financial performance, as shown in the previous table.

What Is Language

1. Describe and define “language.”

2. Describe the role of language in perception and the communication process.

Are you reading this sentence? Does it make sense to you? When you read the words I wrote, what do you hear? A voice in your head? Words across the internal screen of your mind? If it makes sense, then you may very well hear the voice of the author as you read along, finding meaning in these arbitrary symbols packaged in discrete units called words. The words themselves have no meaning except that which you give them.

For example, I’ll write the word “home,” placing it in quotation marks to denote its separation from the rest of this sentence. When you read that word, what comes to mind for you? A specific place? Perhaps a building that could also be called a house? Images of people or another time? “Home,” like “love” and many other words, is quite individual and open to interpretation.

Still, even though your mental image of home may be quite distinct from mine, we can communicate effectively. You understand that each sentence has a subject and verb, and a certain pattern of word order, even though you might not be consciously aware of that knowledge. You weren’t born speaking or writing, but you mastered—or, more accurately, are still mastering as we all are—these important skills of self-expression. The family, group, or community wherein you were raised taught you the code. The code came in many forms. When do you say “please” or “thank you,” and when do you remain silent? When is it appropriate to communicate? If it is appropriate, what are the expectations and how do you accomplish it? You know because you understand the code.

We often call this code “language”: a system of symbols, words, and/or gestures used to communicate meaning. Does everyone on earth speak the same language? Obviously, no. People are raised in different cultures, with different values, beliefs, customs, and different languages to express those cultural attributes. Even people who speak the same language, like speakers of English in London, New Delhi, or Cleveland, speak and interact using their own words that are community-defined, self-defined, and have room for interpretation. Within the United States, depending on the context and environment, you may hear colorful sayings that are quite regional, and may notice an accent, pace, or tone of communication that is distinct from your own. This variation in our use of language is a creative way to form relationships and communities, but can also lead to miscommunication.

Words themselves, then, actually hold no meaning. It takes you and me to use them to give them life and purpose. Even if we say that the dictionary is the repository of meaning, the repository itself has no meaning without you or me to read, interpret, and use its contents. Words change meaning over time. “Nice” once meant overly particular or fastidious; today it means pleasant or agreeable. “Gay” once meant happy or carefree; today it refers to homosexuality. The dictionary entry for the meaning of a word changes because we change how, when, and why we use the word, not the other way around. Do you know every word in the dictionary? Does anyone? Even if someone did, there are many possible meanings of the words we exchange, and these multiple meanings can lead to miscommunication.

Business communication veterans often tell the story of a company that received an order of machine parts from a new vendor. When they opened the shipment, they found that it contained a small plastic bag into which the vendor had put several of the parts. When asked what the bag was for, the vendor explained, “Your contract stated a thousand units, with maximum 2 percent defective. We produced the defective units and put them in the bag for you.” If you were the one reading that contract, what would “defective” mean to you? We may use a word intending to communicate one idea only to have a coworker miss our meaning entirely.

Sometimes we want our meaning to be crystal clear, and at other times, less so. We may even want to present an idea from a specific perspective, one that shows our company or business in a positive light. This may reflect our intentional manipulation of language to influence meaning, as in choosing to describe a car as “preowned” or an investment as a “unique value proposition.” We may also influence other’s understanding of our words in unintentional ways, from failing to anticipate their response, to ignoring the possible impact of our word choice.

Languages are living exchange systems of meaning, and are bound by context. If you are assigned to a team that coordinates with suppliers from Shanghai, China, and a sales staff in Dubuque, Iowa, you may encounter terms from both groups that influence your team.

As long as there have been languages and interactions between the people who speak them, languages have borrowed words (or, more accurately, adopted—for they seldom give them back). Think of the words “boomerang,” “limousine,” or “pajama”; do you know which languages they come from? Did you know that “algebra” comes from the Arabic word “al-jabr,” meaning “restoration”?

Does the word “moco” make sense to you? It may not, but perhaps you recognize it as the name chosen by Nissan for one of its cars. “Moco” makes sense to both Japanese and Spanish speakers, but with quite different meanings. The letters come together to form an arbitrary word that refers to the thought or idea of the thing in

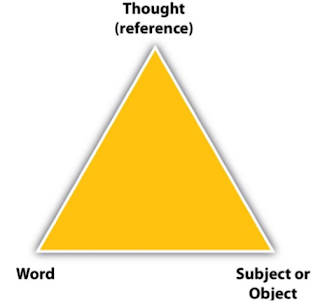

The Semantic Triangle

Source: Adapted from Ogden and Richards

This triangle illustrates how the word (which is really nothing more than a combination of four letters) refers to the thought, which then refers to the thing itself. Who decides what “moco” means? To the Japanese, it may mean “cool design,” or even “best friend,” and may be an apt name for a small, cute car, but to a Spanish speaker, it means “booger” or “snot”—not a very appealing name for a car.

Each letter stands for a sound, and when they come together in a specific way, the sounds they represent when spoken express the “word” that symbolizes the event. For our discussion, the key word we need to address is “symbolizes.” The word stands in for the actual event, but is not the thing itself. The meaning we associate with it may not be what we intended. For example, when Honda was contemplating the introduction of the Honda Fit, another small car, they considered the name “Fitta” for use in Europe. As the story goes, the Swedish Division Office of Honda explained that “fitta” in Swedish is a derogatory term for female reproductive organ. The name was promptly changed to “Jazz.”

The meaning, according to Hayakawa, is within us, and the word serves as a link to meaning. What will your words represent to the listener? Will your use of a professional term enhance your credibility and be more precise with a knowledgeable audience, or will you confuse them?

Business Competencies

Injecting the business development unit with the necessary resources is an important aspect of managing business development effectively. But simply hiring people with a strong track record is not enough."Simply hiring people with a strong track record is not enough"Managing the competences within the unit in coherence with the tasks it is fulfilling is an important part of the management of the business development unit – one that is often overseen. In many cases, people think that by hiring highly capable people, the competences are in place. However, since business development tasks are of such a changeable and complex nature, attention must be put into managing these competences over time and develop them to match the tasks at hand.

1. Competences of business developers

Even though business development units are often quite small (on average between 2-12 people), their tasks and role in the organisation require that they cover a wide spectrum of competences, ranging from specific knowledge about a market or a specific business process to their ability to manage, engage and interact in large-scale change programmes and with people whose commitment is vital for their own success.

Business developers must be multi-faceted; they must be analytically skilled and they must be able to manage big projects and communicate with many different kinds of people. That is why most business developers have very diverse backgrounds, often with industry experience combined with some sort of consulting experience.

"Business developers must be multi-faceted; they must be analytically skilled and they must be able to manage big projects and communicate with many different kinds of people"

To fulfil the roles as strategists, facilitators and/or executors, the following competences are necessary With the diverse range of tasks of business developers, it is impossible for one person to cover all aspects. This is especially true for companies with highly specialised functions. Business developers are not superheroes that can take on many forms to fight the day-to-day battles against evil – nor should they strive to become so. The competences mentioned above are representative of the totality of skills any effective business development unit must possess in some form or shape. The role of the manager is to manage the spectrum of competences so that it matches the tasks that the unit is to carry out.

2. Competences in a BDM context

The range of competences necessary to carry out tasks varies according to the role that the business development unit fulfils in the organisation.

Not all business developers must be excellent strategists, executioners and facilitators at the same time. Neither should they be specialists in project management only. Business developers must be knowledgeable of several disciplines and roles and while being proficient in them all, they must also know how to activate and make use of them through others.

When it comes to the orchestration of strategy management, competences pertaining to being a strategist must be present at all times in a business development unit since this is an ongoing process that has its affiliation in business development. However, when it comes to specific business processes that require specialist knowledge, the business development unit may also draw on competences from outside the unit: from other people within the organisation or from its network of advisers. Examples of this include highly specialised market or product knowledge, jurisdictional or legal resources, accounting and financial specialists, etc.

"Business developers must be knowledgeable of several disciplines and roles and while being proficient in them all, they must also know how to activate and make use of them through others"

The competence spectrum includes the tangible competences that are needed to know how to carry out the tasks. However, to be truly successful, business developers must do more than manage and carry out the tasks set out for them. BDM is also a human discipline that entails a focus on the people that are to adopt, implement and execute the strategy. This includes consideration of the way in which tasks are carried out.

We call these the intangible competences which are often contingent on the personality of the person in question. One such competence is the ability to be creative and think beyond the boundaries of existing markets, products and the organisation.

"The point is not to come up with as many ideas for business development as possible but to come up with a few, valuable ideas"

Being creative is indeed important, but it is not any kind of creativity that is appropriate for business developers. The ability to be creative is valuable when combined with an understanding of the business and an ability to critically analyse and evaluate alternatives. The point is not to come up with as many ideas for business development as possible but to come up with a few, valuable ideas.

Besides "qualified creativity", the other intangible competences that are important in the discipline of BDM are

o Ability to be humble

According to Professor Flemming Poulfelt, Copenhagen Business School: "Business development is too important to be left to business developers"

o Ability to navigate

According to Professor Anders Drejer, Aarhus Business School, business developers must "accept and deal with the insecurity and unpredictability – there is no fixed agenda of business development"

o Ability to engage

According to Professor Anders Drejer, Aarhus Business School: "The need to anticipate the context – the organisational, managerial, cultural and market context – and moving within and in between different contexts is pivotal to business developers"

o Ability to translate

Peter Læssøe, Business Development Director, Nykredit, states that "business developers must be able to talk strategy so that everybody understands it and knows what to do"

o Ability to impact

According to Nicolai Hesdorf, Arla Foods, business developers must be "empathetic tough nuts that are not afraid to state their opinion and speak up"

As with the competence spectrum, it is important to stress that all business developers within a unit need not be excellent in all competences. However, when it comes to the intangible competences, the manager of the unit is an exception. As the face towards the management and the organisation, it is necessary that the manager acts as a role model and contains all these intangible competences or traits.

Having a focus on the competences and on "selling" these competences makes it easier to define and conceive the role of the business development unit within the organisation. However, it also increases the difficulties of delimitating the kind of tasks that are taken on by the unit. Careful attention must be put into ensuring that the role as the connecting link between strategy and execution is fulfilled and that the unit does not become entangled in daily operations.

3. Guidelines for managing competences

To mature the business development unit professionally, start with the people. For talented and high-calibre individuals with a strong career motivation which characterises many business developers today, managing and developing both personal and professional skills is a vital point of succeeding with business development.

"If business development is there to stay, it is there to enter a structured professional development plan on par with all other organisational units within the organisation"Depending on the role of the business development unit within the organisation, some competences will be more important than others. It is the role of the business development manager to co-ordinate and develop these competences so that the unit can solve its tasks successfully at all times. Developing business developers is an integrated task for the HR organisation, yet a completely overlooked area of responsibility for many HR organisations. But if business development is there to stay, it is there to enter a structured professional development plan on par with all other organisational units within the organisation.

We believe the following guidelines can be used to more effectively manage the business development competences

• Revisit the purpose, role and areas of responsibility

‒ clearly articulate the business development role and area of responsibility

• Map the unit's current competences using the competence spectrum

‒ allow for a 1-5 scale to plot both professional and people skills

• Involve HR in constructing a professional development plan individual by individual

‒ using the competence spectrum plot as a point of departure

• Build a compensation scheme that also rewards professional development

‒ allow for inclusion of soft measures in bonus schemes and long-term career planning

• Follow up biannually on needed development points and corrective action

‒ making the most of HR templates, tools and techniques

Being able to mobilise a meticulous set of competences combined with an ability to dissociate oneself from the subject matter is the ultimate role of the business developer. This means that the management of competences becomes an important part of the management process of business development units.

Naturally, the specific competences will vary according to the area(s) of responsibility, and attention must be put into matching competences and responsibilities. Aside from that, competences should be managed with careful attention to the role that the unit fulfils in the organisation.

Thinking Process

SOLUTION-BASED LOGIC

What actions do you and your organization take when formulating a strategy? How does the process begin? When offered the challenge of formulating a strategy, what is your first inclination? Do you instinctively start thinking about the process that you are going to follow, who is going to be involved or do you begin to brainstorm potential solutions? When the team responsible for formulating a strategy is gathered together and given their mission, what actions do they take? What becomes the focus? The process? Structure? Solutions? Let’s say, for example, you were asked to improve your company’s existing product line. What is your first thought? Do you think about several potential new product concepts? What is the first step you will take? Will you talk to customers to see what they want? What if you were asked to improve your company’s order entry process? What is the first step you would take?If you are like most individuals, the immediate focus when involved in formulating a strategy or plan of any kind is the brainstorming of potential solutions. We live in a solution-based world. Most people are solution oriented. From our earliest age, we are taught to find solutions to problems. We are taught to focus on solutions. We have created methods for brainstorming solutions. We are often rewarded for devising good solutions. When our business associates, peers or superiors present us with a problem we often take pride in offering solutions. We are motivated in many ways to focus on solutions.

This solution orientation has set the framework for the high-level thinking strategy that is typically used by organizations when they formulate strategies, define plans and make complex decisions. When attempting to find the best strategy or solution, organizations inherently follow a set logic or a natural sequence of activities. These activities are often executed subsconsciously and shape the organization’s approach to strategy formulation.

The critical steps defining this logic are summarized as follows. Note the order of the steps.

1. First, individuals use various methods to think of alternative ideas and solutions. The methods may include brainstorming, research, talking to customers or other techniques.

2. Second, the individuals on the strategy formulation team discuss and evaluate each of the proposed solutions to determine which solution is best. The methods used to accomplish this task may include the review of supporting data and may involve debate. Intuition and gut-feel may affect the evaluation. Scientific methods such as concept testing, conjoint analysis, quantitative research or other methods may also be used in the evaluation process.

3. Third, the strategy formulation team considers the ideas that are presented and begins a process of debate, negotiation and compromise until the ‘‘best’’ solution is devised.

This logic dictates that individuals in the organization devise alternative solutions, evaluate each solution and then reach consensus on which solution is best. Ask yourself, is this the logic that is followed by individuals in your organization when they are asked to formulate a company strategy, a product or service strategy or a strategy that is needed to improve an operating, support or management process?

The basic premise behind this logic is to first focus on the creation of the solution and to then focus on how well the solution meets the criteria that are being used to evaluate the solution. The key characteristic of this approach is that it starts with the creation of the solution.

In a typical strategy formulation scenario, for example, those responsible for creating a company strategy may be brought together for a series of strategy formulation sessions. Prior to the first session, the participants organize their ideas and solutions and prepare presentations that are intended to communicate their ideas to others and convince them of their value. As the sessions proceed, the participants present their ideas and solutions to the group. The group debates the value of each solution and the presenters defend and support their positions. Team members evaluate the proposed solutions using a variety of methods and criteria. The solutions are debated, modified and negotiated until consensus and agreement are reached.

The underlying logic here again is to devise alternative solutions, evaluate each solution and then reach consensus on which solution is best. This pattern reflects the traditional thinking strategy that is used by many organizations to formulate strategies, define plans and make complex decisions. We call this logic Solution-Based Logic in that it is focused on generating, evaluating and selecting solutions.

The elements of Solution-Based Logic are shown in Figure 2.1. Solution-Based Logic defines the sequence of activities that are commonly performed by organizations when they execute their strategy formulation processes. The use of this logic is instinctive, it is often executed subconsciously.

This logic, or pattern, has been observed in individuals, organizations and cultures around the world. The use of this thinking strategy often goes unchallenged.

Does your organization inherently apply Solution-Based Logic when formulating its company, product, service and operating strategies? Is there an inherent focus on solutions? What problems, if any, does the application of this logic cause your organization?

We will show that the application of this logic, although pervasive, is destructive and prevents organizations from formulating breakthrough strategies and solutions. Challenging the use of Solution-Based Logic is a critical step in evolving the process of strategy formulation

APPLYING SOLUTION-BASED LOGIC

The application of Solution-Based Logic is found in most organizations today. People inherently talk about and focus on solutions. This includes executives, managers, employees, investors, customers, stakeholders and others. This fixation on solutions is what has caused most organizations and individuals to completely overlook the fact that a better way to formulate strategies may exist.

The use of Solution-Based Logic dictates the dynamics that most organizations experience when formulating strategies today. To gain some insight into these dynamics, recall the last time you were involved in an activity in which a strategy, plan or decision was being contemplated. How did the activity start? Did individuals propose solutions that they perceived to be best? Were they then required to convince others of the value of their proposed solution? Did they defend their proposed solutions with a complete set of facts? Were emotions involved? Did they want their solutions to win? Was power, position, recognition or peer acceptance at stake? How were the proposed strategies and solutions evaluated? Was the optimal solution created? Was the optimal solution chosen? What problems arose?

We will demonstrate that the use of Solution-Based Logic inhibits many organizations from formulating breakthrough strategies and solutions. Its use is responsible for the gross inefficiencies that exist in most strategy formulation processes today. Using the algebraic equation analogy, the use of Solution-Based Logic is like guessing the solution to a complex algebraic problem and then testing to see if you guessed the right solution. If you have ever attempted to use this approach when solving a complex algebraic equation, you’ve undoubtedly recognized that guessing is not an efficient approach to problem solving, and there is a good chance that you will never guess the optimal solution.

Most people underestimate the number of possible solutions that are technically possible when formulating a strategy in a given situation. Let’s consider the following example. When formulating a company strategy you must make decisions regarding which market to target, which segment to target, how to position the product or service, which products and services to offer, how the offering should be priced, how to manufacture the product, how to distribute the offering, what the advertising message should be and how the offering should be promoted. Suppose, for the sake of illustration, that the company has only seven alternatives for each of the nine decisions. In reality, of course, there may be fewer than seven alternatives, but there may be more. If there are only seven alternatives for each of the nine decisions, how many different strategies are possible? The answer is not 7 times 9 or 63 different strategies. The answer is seven to the ninth power or 40,353,607 potential strategies. Among all these possible strategies, of course, some would be very successful and some would be disastrous, while most would fall somewhere in between. But what are the chances of an organization selecting the optimal solution from over 40 million possible alternatives? Statistically speaking, they approach zero, especially when you consider the fact that most organizations have a tendency to consider relatively few alternatives.

In Human Performance Engineering (1989), Robert Bailey summarizes his research on ineffective decision making and strategy formulation by stating that individuals involved in the strategy formulation process tend to:

1. Overaccumulate information.

2. Use a fraction of the available information.

3. Hesitate to revise their first options.

4. Consider too few alternatives.

This characterization of the strategy formulation process makes it obvious why most organizations fail to efficiently execute their strategic planning processes and formulate breakthrough strategies. Could these inefficiencies be linked to the use of Solution-Based Logic? As you will see, the answer is clearly yes.

Solution-Based Logic has at least three major drawbacks. These drawbacks affect the way a strategy is formulated and diminish the effectiveness of the resulting strategy. They negatively affect the dynamics between people within the organization. They are the cause of unnecessary friction and inhibit the creation of value. The three major drawbacks are defined as follows

The first major drawback is that the use of this underlying logic and a fixation on solutions places people in a defensive position and prevents them from focusing on the creation of value. By definition, when using Solution-Based Logic, people first come up with solutions. Whether people are asked to propose an idea or solution, or if they propose one on their own, they know they will have to present their idea to others and convince them of its value. At this point, the act of simply proposing an idea or solution triggers an interesting but unfortunate set of dynamics. When proposing an idea or solution, individuals are put into a position where they must defend their proposed solution. As a result, not only will their ideas be judged, but they will be judged personally as well. Their proposed solution, and their ability to convince others of its value, now becomes a matter of personal concern. Many people believe that if their peers accept their proposed solution, it will signify they are competent, creative and deserving of respect. If it is not accepted, they may feel they have failed. Their ability to present and defend their proposed solutions suddenly becomes tied to protecting their own perception of self-worth.

As a result, people often do what they have to to defend their ideas. Individuals actively look for information that supports their proposed solutions. They may conceal information that refutes their position. They may use information out of context to support an idea.

People may even create or fabricate information that supports an idea or proposed solution. When people become defensive, they may not be focused on the prime objective of creating customer and stakeholder value. They are often more concerned with their careers and personal well-being. Being placed in a defensive position does not always bring out the best human qualities.

In some organizations, individuals intentionally pit people against other people or functions against other functions to see who can defend their position the best. The strategy that is defended the best often becomes accepted for implementation. This approach is unlikely to produce a breakthrough strategy, but it is likely to create bad feelings and deteriorate working relationships.

Why do organizations accept this somewhat barbaric approach to strategy formulation? What are their alternatives? Would organizations be better off if individuals worked toward the common goal of creating value without being subject to pressures that motivate them to behave in a defensive manner? A change in logic is required to make this possible.

A second major drawback of Solution-Based Logic is that it does not set out to create a basis for agreement. In fact, its use provokes unnecessary debate and causes disagreement when solutions are evaluated. The debate and disagreement occur because people are focused on solutions and rarely take the time to define and agree on the criteria that is to be used to evaluate the proposed solutions. As a result, they lack a basis for agreement. If an organization cannot agree on the criteria that should be used to evaluate the potential of a solution, then they will certainly not be able to agree on which solution is best. With a fixation on solutions and a motivation to quickly reach a conclusion, organizations rarely take the time to define and agree on the criteria that should be used to evaluate proposed solutions.

Again, think back to the last time you were involved in an activity in which a strategy, plan or decision was being contemplated. Did each person have their own criteria by which to evaluate proposed solutions? Did that criteria favor their proposed solutions? Did the organization take the time to gain agreement on which criteria should be used to evaluate the proposed solutions? Did each person in the room have a different understanding of what your customers valued, what constraints the company faced and what competitive position was desired? Did everyone agree on the criteria that were being used to determine which proposed solution was best? Were decisions based on facts? Was agreement reached on the chosen solution? Was consensus achieved? Was everyone committed to the solution?

The use of Solution-Based Logic does not provide an organization a basis for agreement. The criteria to be used to evaluate the potential of each solution are seldom agreed on. Instead, people have a tendency to use the criteria that support their position so the solution they are defending will win. They often define the criteria with this purpose in mind. Individuals present the benefits that their strategy will deliver and emphasize the importance of those benefits. They rarely identify other important requirements that the strategy will not satisfy. The criteria, or facts, that individuals use to support their proposed solutions may be incomplete, inaccurate or they may not be agreed on. These inefficiencies cause unnecessary debate and are not conducive to the formulation of breakthrough strategies and solutions.

When using Solution-Based Logic, how likely is it that consensus will be reached? More important, how likely is it that a breakthrough solution will be discovered? How can an organization expect to formulate a breakthrough strategy if it does not have or agree on the facts or criteria that should be used to evaluate the potential of alternative solutions? How will the organization ever know what solution is best?

Making decisions without a complete set of facts often results in failure. In his book titled New Product Development (1992), George Gruenwald states that ‘‘between one third and two thirds of all new products that are introduced result in failure.’’ This does not include the hundreds of products that are developed but never introduced. Can this be any indication as to what percent of all strategies, plans and decisions result in failure? What is your organization’s success rate? What, if any, was the cause of failure in any of your company’s recent business, product, service or operational strategies? According to many sources, poor planning is cited as the single biggest reason for the failure of company, product, service and operational strategies. Poor planning often results from an organization’s inability to gather, structure and process factual information. The use of Solution-Based Logic inhibits the effective execution of the planning process and can be cited as a cause of poor planning.

So why do organizations attempt to formulate strategies without having a basis for agreement? What are the alternatives? Would organizations be better off if individuals could work toward the common goal of creating value in an environment where everyone agreed on the criteria that is being used to evaluate the solutions that are proposed? Again, a change in logic is required to make this possible.

A third major drawback of using Solution-Based Logic is that it does not provide a means to quantify the potential of a proposed solution or enable an organization to determine if a breakthrough solution has been created. As a result, an organization may come across a breakthrough solution and never know it. They may unknowingly reject it in favor of a less attractive solution. This can happen because the individuals involved do not know what criteria define a breakthrough solution. They are focused only on defending the solutions they initially proposed and rarely know what constitutes value in the eyes of the customer or the company. As a result, they never know how much value a proposed solution is capable of delivering.

Recall again the last time you were involved in an activity in which a strategy, plan or decision was being contemplated. Did all those involved believe they had created a breakthrough solution? Did everyone know why one solution was better than another? Did everyone agree on how to make a solution better? At what point did you stop searching for a better solution? Was the optimal solution proposed? Would anyone have known if the optimal solution had been proposed? How did you set out to create the optimal solution?

The use of Solution-Based Logic often precludes the creation of the optimal solution. The criteria that define the optimal solution are often unknown. Therefore it is difficult, if not impossible, to know if the optimal solution has been created. To make matters worse, organizations tend to evaluate only a few alternative solutions out of the thousands or millions of potential solutions that exist. This makes the prospect of formulating a breakthrough solution even more unlikely.

How many alternative solutions did you consider in your last strategy formulation exercise? Five? Eight? A dozen? In any strategic situation, there may be hundreds, thousands or even millions of potential solutions in the universe of possible solutions. You know that the optimal solution does exist. But what is the chance that one of the dozen or so proposed solutions is actually the optimal solution? And if it was, how would you know? The fact is that the random creation and selection of the optimal solution is unlikely. It is as unlikely as guessing the answer to a complex algebraic equation.

The use of Solution-Based Logic is mainly focused on creating, defending and negotiating solutions. The use of Solution-Based Logic puts people in a defensive position, it does not provide a basis for agreement, and it does not provide a means to determine if a breakthrough solution has been created. These are just three of the major drawbacks of using Solution-Based Logic in the process of strategy formulation.

Before we continue, I would like you to contemplate the following. Unfortunately, many strategies are categorized as failures only after they have been introduced or implemented costing the company time, money and profits. But ask yourself the following question. If a strategy or solution can be classified as a failure after it is introduced, what is preventing an organization from knowing it is going to fail in advance of its introduction? According to what criteria did it fail? If those criteria were known, and used to evaluate the potential of the concept to begin with, could its eventual failure have been predicted in advance? Could the failure have been avoided altogether? Contemplate how this may be possible as we continue on with our explanation of Solution-Based Logic.

TRADITIONAL STRATEGY FORMULATION SCENARIOS

The scenarios stated below highlight some of the activities that transpired during planning sessions that employed traditional strategy formulation methods. The scenarios, which are based on actual experiences in companies that will remain unnamed, demonstrate the application of Solution-Based Logic and its impact on the execution of the strategy formulation process. The drawbacks of using this approach are also described for each scenario.

Scenario 1: Formulating a Division Strategy

Division management of a Fortune 100 company was given its annual task of formulating an operating strategy for the division. To ensure the participants remained focused on this important activity, the president of the division scheduled a three-day meeting at a resort hotel in Aspen, Colorado.

The president chaired the session. The vice-presidents of each major function were asked to attend along with the lab director and a legal advisor. The participants were asked by the president to present their ideas for a division strategy. As the session began, the president gave an overview of recent company performance and informed the team of his goal to increase division sales by 20% and profits by 10% per year for the next five years. The challenge to the 12member team was to define and agree on a strategy that would enable the achievement of these goals.

Knowing what was expected, several participants were prepared to present their proposed strategies to the group on the first day. Four executives offered their ideas and proposed four alternative strategies. It became evident that the proposed strategies were not only devised to meet the presidents’ objectives but were also intended to enhance the careers of those proposing the strategies.

Members of the group asked the presenters several questions regarding their proposals. Some questions were intended to clarify points. Other questions were intended to debunk, discredit and ridicule the strategies that were being proposed. After each presentation was made, the participants debated the merits of the proposed strategy. It was obvious that each participant evaluated the proposed strategies from a different perspective. Few positive comments were made as most of the effort was focused on finding the holes in the proposed strategies. The strategies that were proposed conflicted with each other. Each strategy was challenged. When questioned, the executives used whatever tactics they knew to defend their proposed strategies. They were well armed with financial data and used it to convince others that their proposed strategies would meet the aggressive financial objectives set by the president. They wanted to ensure the elements of their strategies were accepted. Each team member used different criteria to evaluate the potential of the proposed strategies. As a result, the strategies were debated, refined and negotiated in an attempt to obtain consensus. Participants with the most staying power, persuasive presentations and the loudest voice faired best in convincing the others of the merits of their proposed strategy.

For two and a half days, the various functions debated the value of each proposed strategy. Few new alternative strategies were introduced. The participants, however, had difficulty reaching an agreement. With three hours remaining on the third day, the president stepped in and made several key decisions that were required to break the remaining cross-functional deadlocks. Once these decisions were made, the participants, realizing that time was running out, worked together to gain consensus on a strategy. The chosen strategy was shown to meet the organization’s financial objectives. It was to be documented over the following days and sent out for final review and signatures.

After the three-day session was complete, several team members spent a day or two skiing together. A couple of participants were overheard talking about proposing changes to the agreed-on strategy when it came around for final review.

Analyzing Scenario 1

As stated by Gary Hamel and C. K. Prahalad in Competing for the Future (1994), ‘‘in many companies strategy means turning the crank on the planning process once a year.’’ They go on to say that ‘‘typically, the planning process is more about making numbers add up.—This is the revenue and profit growth we need this year, now how are we going to produce it?—Than it is about developing industry foresight.’’

The example stated above is no exception. It was an attempt to formulate a strategy that would enable the organization to meet its financial objectives. In formulating this strategy, the participants followed the sequence of events dictated by Solution-Based Logic. Their first focus was to propose several strategies or solutions. The strategies were then discussed and evaluated using criteria that were incomplete and not agreed on. The strategies were then negotiated and compromised to reach a conclusion.

The participants did not agree among themselves on the criteria that define a breakthrough strategy. In fact, they never attempted to agree on a set of evaluation criteria. They spent most of their time defending their proposed strategies with the information they had prepared. The debate did not address which customers should be targeted, which customer requirements were most important or which competitive position they desired. They had access to financial information and used it to produce a financial-driven strategy. They did not have access to the information they needed to create a customer-driven strategy. As a result, the strategy they created was less than optimal at creating customer value. The team did not have all the facts that they required, nor did they establish a basis for agreement.

As time ran out, the proposed strategies were negotiated and compromised so that agreement could be reached. In reality, the strategies were negotiated and compromised to the point where they were void of true commitment. Each executive was forced to give up something they believed to be important. Politics, gut-feel and emotion drove the final result. Facts did not play a major role in supporting the chosen strategy. It is important to ask what percent of the decisions made in this process were based on 100% of the facts. In a subsequent conversation, several members confessed that maybe 10% to 20% of the decisions were based on 100% of the facts. Others suggested that it was less than that.

As stated by Bradley Gale in his book Managing Customer Value (1994),

Management by fact is the path to competitive advantage. Yet, many companies cannot really manage by fact. Executives from different parts of the business speak different languages. The result: the team fails to achieve fact-based consensus, and the ‘‘boss’’ ultimately makes decisions based on his or her own subjective criteria.

The use of Solution-Based Logic often drives an organization down an unproductive path. The scenario stated above could be varied in numerous ways and still have many of the same limitations. Scenarios like the one stated above portray a real picture of how strategic planning activities are conducted in many organizations today. Organizations typically lack the structure, information and processing power that is required to formulate breakthrough strategies and solutions, and they inherently apply the use of Solution-Based Logic.

Scenario 2: Formulating a Product Strategy

A product planning team in a Fortune 100 company was given the responsibility of defining a product strategy for its company’s main line of products. The project manager chaired a series of product planning sessions that took place over a one-month period. The new products were required for introduction within 12 months.

The participants included planners, engineers, managers, sales people and, occasionally, company executives. Prior to the sessions, many of the participants talked to customers to obtain their requirements. These requirements, which included lists of solutions, features and specifications, were used by the participants as the basis for creating alternative product concepts.

A marketing executive came to the first session to propose a product concept that resulted from a conversation that took place with a potential customer on an airplane two weeks earlier. The potential customer told the executive that if his company’s product had a specific feature set, it would be much more appropriate for use within his organization. The executive, acting with good intentions and focused on customer satisfaction, promised the potential customer that it would be resolved.

As the first planning session continued, the planners, engineers and others proposed the product concepts they believed would best satisfy the customers’ requirements. Their concepts closely reflected the solutions that were requested by the customers to whom they had talked. It was found that the requirements captured by one participant often conflicted with requirements captured by other participants. Some customers wanted one solution, and others wanted alternative solutions. A large part of the planning activity involved the debate and discussion of these conflicts. They did not establish a basis for agreement but rather focused on defending the concepts they proposed.

As the second session began, the debate continued. The presenters were armed with new information and used it in an attempt to defend and gain support for their initially proposed solutions. The participants with the most staying power, political clout, persuasive presentations and the loudest voices faired best in convincing the others of the merits of their proposed product concepts.

After much debate and using subjective evaluation criteria, the group reduced the number of concepts under consideration to just three. Not everyone agreed that the best three concepts were selected. Unfortunately, for mostly political reasons the executive’s proposed concept was accepted by the participants as one of the top contenders. At this point, the top three concepts were documented, prototyped and prepared for concept testing with customers in a focus-group environment.

Three weeks later, the three prototyped concepts were presented to the focus group participants, and they were asked to choose which one they believed delivered the most value. After concept testing was completed, the team members met to review the findings. Upon reviewing and debating the results, they chose to develop the concept that received the most favorable review. They then began to design and develop the concept.

In addition to concept testing, the planning team also elected to conduct conjoint analysis, which is a specialized form of market research that enables an organization to determine which combination of attributes are preferred by various segments of the population at various price points. Although it would take up to four months to complete this research, the results would be used to confirm the best concept had been chosen.

Analyzing Scenario 2

The participants followed the sequence of events dictated by Solution-Based Logic. Their first focus was to propose several product concepts. The concepts were then debated, defended and were eventually negotiated and compromised to narrow the number of concepts under consideration to just three.

The participants used requirements they captured from customers as the basis for many of their proposed concepts. Many of the requirements that were captured simply described solutions and features that the customers requested. Unfortunately, customers are rarely technologists, engineers or strategists, and they seldom invent. Following their advice often leads to the creation of me-too products. In any case, the participants took the customers’ words as gospel and fought to defend the solutions that they heard their customers request. Each proposed concept was defended with customer inputs. The debate often degraded to the point where participants tried to discredit a concept based on which customer the inputs came from.

To nobody’s surprise, the marketing executive’s idea was placed high on the list of valued solutions by the planning team. They felt politically obligated to do so. The solution that the executive supported may have taken care of the potential customer that made the suggestion; but many participants recognized that if it were developed, it would negatively impact other customers, curtail the company’s production capabilities and impact the development of other offerings that were already planned. Many participants secretly hoped that this concept would not be selected. They admitted that it was not the first time that this executive reacted to comments made by a potential customer. The solution may have been promised by the executive with good intentions, but it worked its way through the product planning process for the wrong reasons. The team did not have the information it needed to refute the concept proposed by the executive; therefore, the team had little choice but to consider it as one of the top concepts.

The team failed to establish a basis for agreement, and they did not gain consensus on what the customers valued. As a result, they failed to agree on which concepts were best. The project manager ended up making a unilateral decision in selecting the top three concepts, but as he said, ‘‘that is why I get the big bucks.’’

Once the concepts were narrowed down to the top three, they were evaluated using concept testing. In conducting this test, customers were asked to evaluate three concepts out of thousands of possible solutions. They were asked to choose which of the three they perceived to be the best. It is possible that the customers were evaluating three highly valued concepts. It is also possible that they were evaluating concepts that were not valued at all, yet they were forced to choose the one they preferred. This type of testing may or may not result in the selection of a product that will be accepted in the market place. When conducted as stated, concept testing is a high-risk approach to product planning and strategy formulation. To make matters worse, several team members suspected that the concepts selected by the project manager for evaluation were pet projects that were easy to implement. They were not convinced that the decisions made to select the top three concepts were based on a complete and accurate set of facts.

The product planning team also elected to conduct conjoint analysis. As part of conjoint research, participants are asked to trade-off between several attributes that are part of a complete concept. The major drawback of conjoint analysis is that it assumes a solution and the attributes associated with that solution. It does not make provisions to determine if the solution that is assumed is a valued solution. An organization may be sorting out the best attributes for an eighttrack tape player, while its competitors are developing a compact disc or DVD player. As another possibility, an organization may be focused on the right product, but may be evaluating unimportant or trivial attributes.

This scenario portrays a real picture of how product-planning efforts are conducted in many organizations today. The use of Solution-Based Logic makes people defensive, fails to establish a basis for agreement and makes it difficult to know if the optimal solution has been created or chosen. Combine this with the fact that most organizations also lack the structure, information and processing power they need to formulate strategies, and it is no wonder why most new product efforts fail. In fact, this characterization of the strategy formulation process puts into perspective why most organizations rarely formulate breakthrough strategies and solutions.

So why do organizations attempt to formulate strategies in an environment where people are defensive, lack a basis for agreement and do not know when they have created a breakthrough solution? What are the alternatives? Would organizations be better off if individuals could work toward the common goal of creating value without facing the complexities associated with the use of Solution-Based Logic? A change in the underlying logic that is commonly used to formulate a strategy is required to make this possible.

DRIVING THE INTELLECTUAL REVOLUTION WITH OUTCOME-BASED LOGIC

We are only prisoners of our past if we let previous experiences limit our ability to accept new ideas and new ways of thinking. Sometimes, we must simply give ourselves permission to challenge our existing paradigms and recognize that change is exciting and can provide a source of energy, creativity and motivation. As we will see, changing the way we think about the process of strategy formulation offers many new opportunities. This transformation begins with the introduction of Outcome-Based Logic.

Outcome-Based Logic is an alternative high-level thinking strategy that offers a different approach to the process of strategy formulation. This approach challenges the use of Solution-Based Logic altogether. It redefines the sequence of activities that take place when formulating strategies and solutions. It enables an organization to overcome the limitations that are associated with SolutionBased Logic and breaks down the natural barriers that often stand in the way of creating breakthrough strategies and solutions. The discovery of OutcomeBased Logic resulted from the application of modeling and pattern detection techniques that I used to study the process of strategy formulation. We will discuss these techniques in more detail in the next chapter. This new logic was discovered after years of observation, and it lays the foundation upon which the future of strategy formulation has been built.

So, what is Outcome-Based Logic?

Simply stated, Outcome-Based Logic is a high-level thinking strategy that drives an organization to focus on outcomes rather than solutions.

The critical steps defining this logic are summarized as follows. Again, note the order of the steps.

1. First, individuals within an organization uncover, document and prioritize the outcomes they want to achieve. The outcomes are a list of criteria that describe what the organization would ideally like to achieve with the strategy or solution that is being contemplated. This may require them to consider the outcomes of the company and its customers, company constraints and competitive factors.

2. Second, individuals use the list of prioritized criteria to systematically create, brainstorm and develop alternative strategies and solutions. The same criteria are then used to evaluate the potential of each alternative solution.

3. Third, the results of the evaluations are used to optimize the already proposed solutions until the optimal solution is discovered. The result is often a breakthrough solution.

In contrast to Solution-Based Logic, which focuses on generating solutions first, Outcome-Based Logic focuses first on defining and prioritizing the criteria that will be used to create and evaluate any potential solution. It is important to emphasize that the first step does not involve the creation of solutions. The first step involves uncovering and prioritizing the criteria that will be used to create and evaluate the proposed solutions. The criteria that are established describe, in priority order, what outcomes the optimal solution would satisfy and the degree to which they would be satisfied.

Once the criteria are defined, the next step is to use them to assist the organization in systematically creating a number of alternative strategies or solutions. The concept is simple, if you know what outcomes the optimal solution must achieve, then it makes sense to use that information to create a solution that will produce the desired result. When formulating a company strategy, for example, if you know the optimal solution must enable the organization to minimize the time it takes to ship products, then it would make sense to formulate a strategy that would incorporate a mechanism that enables overnight shipment. Otherwise, the solution would not deliver the value that is desired—or achieve the desired outcome. Or when formulating a product strategy, for example, if you know that portable radio users want to minimize the number of unauthorized recipients who can intercept their communications, then it would make sense to devise solutions that prevent communications from being intercepted by any unauthorized individual. The point is that you know how value is defined. Efforts can then be focused on creating that value. So, once the criteria are uncovered, the objective is to define several alternative solutions that satisfy the stated outcomes. The criteria are used to guide the creation of the solutions.

Once several alternative solutions are defined, an organization can evaluate them against the same criteria to determine which proposed strategy or solution is best. The criteria provide a means to conduct an effective evaluation of each solution. The organization must simply determine the degree to which each proposed solution satisfies the stated criteria to determine which solution is best.

The third step in the application of this high-level thinking strategy is to use the results of the concept evaluations as a means to create the optimal solution. This concept optimization activity involves the proactive elimination of the weaknesses identified in any previously evaluated solution. For example, if a proposed solution is weak in a certain dimension, then other proposed solutions are analyzed to determine if they have the ability to overcome that weakness. The positive elements of each solution are systematically combined to create new solutions that possess even greater levels of value. After several iterations of improvement are completed, the optimal solution is identified.

The concept of Outcome-Based Logic can be summarized in Figure 2.2. It should be noted that this approach is different from Solution-Based Logic in that all the criteria that describe the optimal solution are first defined, and then the search begins to find or create the solution that will best satisfy that criteria.

This is a transformation in logic in that it requires an individual to first define what outcomes the optimal solution must achieve, and then work to create it. It will be demonstrated that the use of this logic drives a set of dynamics that are conducive to the creation of breakthrough strategies and solutions.

Referring back to the algebraic equation analogy, the use of Outcome-Based Logic is like setting up a complex algebraic problem, plugging in the constants, and then systematically solving the equation. The optimal solution is discovered when the equation is solved.

APPLYING OUTCOME-BASED LOGIC

The application of Outcome-Based Logic enables an organization to formulate breakthrough strategies and solutions as it eliminates the three major drawbacks associated with the use of Solution-Based Logic. Individuals no longer have to be defensive. It establishes a basis for agreement and it provides a structure by which the creation of the optimal solution can be verified. In addition, it enables individuals to work together to create value. This dramatically changes the dynamics that are involved in the process of strategy formulation. The discovery of this high-level logic was a major step toward the creation of an advanced strategy formulation process. Let’s analyze the impact that this logic has had on the dynamics of the strategy formulation process.

First, the use of Outcome-Based Logic enables individuals to be inventive rather than defensive. It ensures that all the required criteria, or outcomes, are uncovered in advance of creating any potential strategy or solution. In other words, all the outcomes the organization wants to achieve with the optimal solution are known by all in advance of creating or evaluating a solution. For example, suppose that it is determined and agreed that a new company strategy must enable the organization to achieve the following seven outcomes. Of course, in the real world there may be up to 300 outcomes; but to illustrate this point, let’s assume that the optimal strategy must enable the company to:

1. Minimize the time it takes to bring products to market.

2. Deliver products that are ordered by a customer faster than they could be delivered by any competitor.

3. Minimize the time it takes to respond to inquiries that are made by customers.

4. Improve the company’s financial performance within 12 months.

5. Increase the production yield to 98%.

6. Improve overall employee satisfaction.

7. Offer products that provide more value than the products offered by any competitor.

If everyone knows that value can be created for the organization and its customers by formulating and executing a strategy that would enable the organization to satisfy the stated outcomes, then the efforts of individuals can be focused on devising such a strategy. The pressures that drive individuals to act in a defensive manner are eliminated because:

1. Contributors are asked only to document and submit their inventive ideas on how to satisfy the stated criteria.

2. The potential of each proposed strategy or solution is evaluated by individuals who honor the already-agreed-on evaluation criteria.

3. The evaluation phase does not necessarily require the presence of the individual proposing the solution.

4. Contributors are not judged on their ability to present and defend their solutions.

5. Contributors do not have to uncover new information to support their proposed solutions or hide information that may point out a weakness.

When using this thinking strategy, individuals are focused on the criteria that define the creation of value, and as a result they do not waste their time devising or defending solutions that satisfy other less important criteria. They can effectively focus their knowledge on being inventive. The proposal of an idea or solution no longer turns into a personal quest for approval and acceptance. Individuals can simply propose ideas for others to evaluate against criteria they all agree on. They are now free to create and test their own ideas against criteria that define the creation of value.